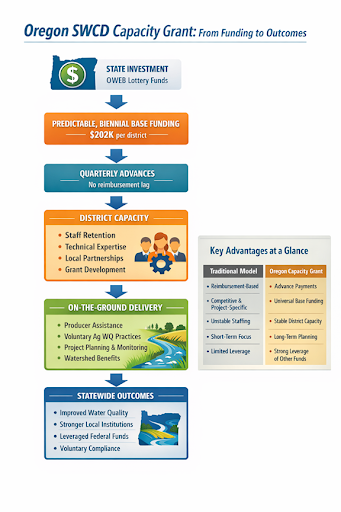

Across the country, state agencies face a persistent challenge: how to finance conservation work in a way that is stable, accountable, and effective over time. While many states struggle with fragmented resources, Oregon has pioneered an Operating Capacity Grant model (found at the bottom of the article). By providing reliable, foundational funding, Oregon allows its soil and water conservation districts (SWCDs) to focus on their mission rather than financial uncertainty.

A large percentage of the nation’s conservation districts rely on a patchwork of short- term, reimbursement-based financial support. This model requires districts to cover upfront costs and scale services up or down based on grant availability. The result is fluctuating staffing levels, inconsistent technical assistance, and a start-and-stop approach to producer engagement.

Nationally, most states draw from five primary revenue sources to support conservation districts:

- Federal funds, such as NRCS program grants, which are typically project-based and

reimbursed after work is completed. - Competitive state grants that are often annual and program-specific.

- Local government contributions that can be uneven or politically vulnerable.

- Limited local taxing authority in some states.

- Short-term private, nonprofit, and fee-for-service revenue.

In contrast, the Oregon Department of Agriculture (ODA) and the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board (OWEB) coordinate a grant program that delivers a dependable, biennial base allocation to every district. This supports the underlying work—staffing, planning, and coordination—that allows watershed restoration and agricultural water quality projects to move forward.

Key features of Oregon’s model:

- Upfront Funding: Grants are disbursed at the start of each quarter, eliminating cash-flow barriers common in repayment-only systems.

- Non-Competitive Access: All 45 Oregon SWCDs are eligible for the grants. While they must meet administrative requirements, the grants, approximately $202,000 per biennium—a two-year grant cycle—are essentially guaranteed.

- Flexibility: With some restrictions, districts can tailor activities to local needs.

Cash flow remains a persistent impediment for conservation districts nationwide. Many districts lack taxing authority—14 of Oregon’s 45 districts have a local tax base—and reimbursement-only models can force districts to delay hiring and reduce services.

“These advances allow districts to keep the lights on, make payroll, and develop projects on the ground with producers and other land managers,” said Karin Stutzman, program lead for the Oregon Department of Agriculture’s Soil and Water Conservation District Program. “It’s not a reimbursement—it’s a base set of funds, which is a major advantage compared with states that don’t have any base level of funding.”

Ray Monroe, manager of the Tillamook County Soil and Water Conservation District, said the grants play a critical role statewide. “This biennial funding source provides essential resources that enable districts to conduct effective outreach within the agricultural community and to offer both technical and financial assistance to landowners and producers.”

The grants are funded through OWEB and financed primarily by dedicated Oregon

Lottery funds. By law, the funds are restricted to activities that:

- Protect or restore native fish and wildlife habitat.

- Protect or restore natural watershed functions to improve water quality or streamflow.

- Implement and manage the Agricultural Water Quality Management Area Plans.

- Support the planning, design, monitoring, and technical assistance required to carry out that work.

Guided by those requirements, districts submit detailed work plans to OWEB that outline how funds will be used and how progress will be measured. Districts distribute capacity funding across standardized categories—including technical assistance, monitoring, partnerships, staff training, and landowner engagement—while ensuring initiatives are customized to meet local priorities and watershed demands.

The practical impact of this funding is seen through the Harney Soil and Water Conservation District’s experience. District manager Jason Kesling said, “Harney SWCD has received ODA capacity funding for many years.” He explained that the grant offers “essential upfront resources to cover staff salaries and project coordination.” Kesling further highlighted the advantage of this model over others, stating, “Unlike typical cost-reimbursement grants, this predictable funding ensures we can meet our expenses without cash-flow barriers.”

“In a large geographic area like Harney County, this stability is vital for retaining experienced staff and maintaining the flexibility needed to provide consistent, high-quality technical assistance and customer service to our landowners,” Kesling added.

In Tillamook County, “the funds directly support technical assistance for numerous field-based conservation practices, such as manure management improvements, animal exclusionary fencing, off-channel watering systems, and tree and shrub establishment,” Monroe said. He noted that these initiatives ensure that “agricultural operations remain in compliance with state and federal regulations while protecting natural resources and promoting long-term agricultural sustainability.”

Oregon’s approach evolved over time from a mix of small, project-specific grants and federal partnerships that often neglected essential operating costs. In 1999, the Oregon Legislature established OWEB to invest state resources, including state lottery funds, into conservation. Following passage of Measure 76 in 2010—which restricted direct fund transfers—OWEB and ODA established a 2011 interagency agreement to administer capacity grants in their current form.

Today, OWEB manages funding, rules, and accountability, while ODA ensures district work aligns with Oregon’s Agricultural Water Quality Management Program and state law. This arrangement strengthens accountability, improves interagency coordination, and ties district operations directly to statewide watershed priorities.

The Oregon funding model demonstrates that how conservation is funded is just as critical as the amount invested. By prioritizing operating capacity and providing upfront financial resources, the state has built a proven alternative to traditional reimbursement approaches—one that could serve as a national blueprint for conservation funding.